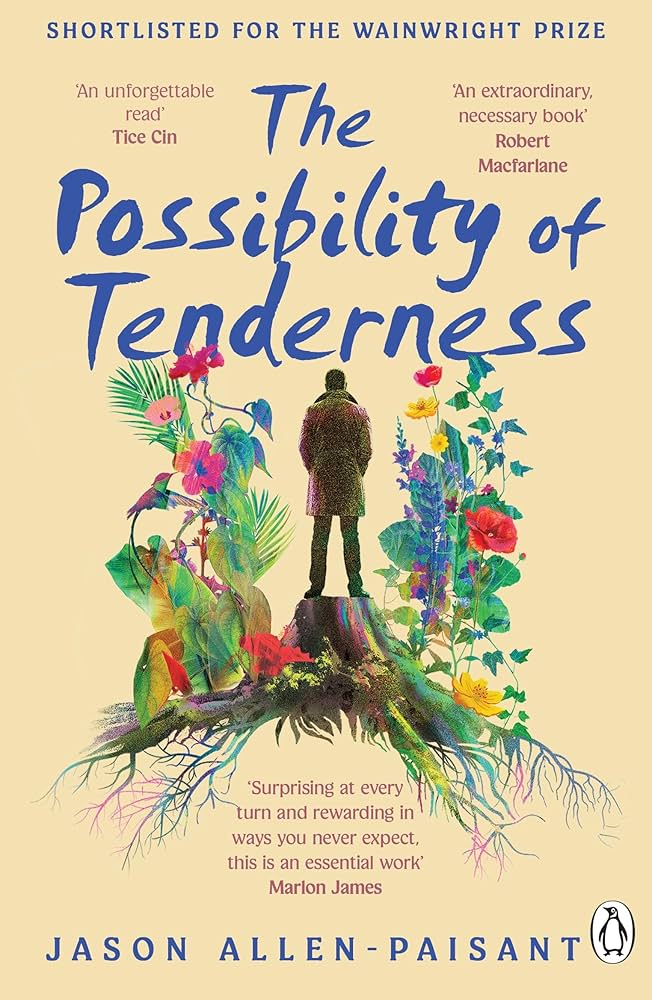

Book extract | The Possibility of Tenderness: Jason Allen-Paisant

STORIES

I’ve just walked past a section of the wood that I hadn’t visited in years, perhaps not since the days of the pandemic. I see an overturned tree. A slope. Lots of red leaves. And then the coolness of a spreading tree, the protectiveness of the long limbs. It was there that Leyla and I stopped on a series of days during the first lockdown. And what I remember most is Leyla playing, oblivious of the aggressions that her dad contends with daily. I remember her pram; I’m surprised that I managed to come all the way here with it. The determination it took to push that pram over all the roots of all the hills, in between tight spaces, over rocky ground, to get all the way here. Or perhaps it was a kind of obliviousness, a kind of ignorance of the reasons why one would not do such a thing. I’m so surprised at how natural we were, how comfortable we were here. Leyla, at two years old, walked astonishingly long distances. Was it the restrictions of the pandemic that taught her how to walk for so many miles?

I’ve passed the spot where she and I used to rest. But now I stand up on a tree, reflecting back on that spot where I see Leyla in the negative of this memory’s film reel. What strikes me most is the fullness of her contentment, her indulgence in the childhood joy of being in this space. I see Leyla with her Afro, her slightly buck teeth, her rubicund face, the glittering pools of her smile. I hear her parakeet laugh, the sound of her feet pattering on the ground of the slope. She plays under the tree, with leaves, touching bark, rubbing her hands over things.

I see both of us playing hide-and-seek in this pandemic wood. I also see all the people who pass. Family after family, they feel this familiar feeling of stuckness, of having nothing else to do but come out. They discover spaces of the backwoods into which they would not ordinarily have come. They’re passing the time. They pass us. Only a look or a swift dart of the eyes acknowledges that we’re here. English awkwardness. Leyla, oblivious. The fullness of her play becomes even fuller in that moment. Stark relief, childhood play. In the negative of this film, I am thrilled for the thriving of my daughter in the green space.

Jason Allen-Paisant, photo by Ferrante Ferranti

It’s my first time round here in well over two years. I’m standing on an overturned tree. I’m sitting now, so as to be less threatening to the people passing by. I’m sitting down on the tree to love the tree, but also to more easily occupy my space. The tree seems so undead. All that I said above, I said while standing on the trunk. I went up on the trunk, thinking. This was my way out of history.

On this winter weekday morning, I see well-formed trails and beaten footpaths, but no people. Slipping back to that winter I first set foot in this place, I see the floor of dry leaves that glinted like so many coins. Today I’m going the full distance of a trail I used to take during the pandemic, often running, sometimes walking with Leyla or by myself.

It’s so strange, when you think about it, for me to be here, walking. For me to be out of Coffee Grove and here in Leeds, walking, not with my goats but just walking. Living in a house in Leeds is already far away; walking in these woods is like being on another planet. And yet . . . My life is now wedded to this place. Both my children were born in this country. I’m opening myself up now to the possibility of tenderness in this soil of transplantation. To the idea that I might somehow walk here the way I learned to walk as a child. Somehow. Through some means. It might not be here in the park, but it might be somewhere out there with new friends.

It’s approaching dusk. I’m standing on a bend in a narrow walking path, typing notes on my phone, a possible segment for a book. A young man with a walking pole approaches, he’s upon me before I even hear him. The dried leaves crackle under his footsteps. He looks down. He looks into the shrubbery of holly; he asks all the holly to welcome his body. What would have happened if we’d said hello to each other? I resume walking, then stop again to type, and after quite a while I hear the sound of wood on rock and turn around. An old Black man is approaching behind me. I continue typing. I am exhilarated. He does not look at me, he does not say hello. He sends his walking stick, and his eyes, into the ground. But I will not miss the opportunity to speak to him, and to myself. I say, Sir, I’m glad to see you here; it means everything to me. He cracks a very reluctant, sheepish smile, nods and keeps on walking. I recall now one of the questions I posed to myself earlier: whether beauty isn’t a story we tell to ourselves, about ourselves. And indeed, the story I’m telling to myself, about myself, now, is this: I’m glad to see you here.

I continue my walk, arriving at a slope surrounded by densely packed trees. I’m meditating on the rhododendrons running like snakes, and a woman overtakes me with her canine in hand, looks back and smiles good morning, as if to say it’s pleasant to see that you, too, are here, as if to say well done, you’ve done what’s needed. Stay here. It’s good for you. And I think, this is what it is to rest. This is what Mama was seeking; what my mother, too, was seeking. Rest. The ability to be here, to walk through the woods, on the leaves. The ability not to think of space, but to inhabit it – unhindered, unbarred. Through the numerous trunks of trees, under the bellies of rhododendrons. Time is not upon us – the woman’s good morning is a shared affirmation of rest. I’m in it. And I had never imagined what it might be.

Jason Allen-Paisant will be in conversation with Edward Adonteng on Tuesday 3 March, 7pm: book tickets