Seeds of Exchange: Mak Sau 麥秀, Whang At Tong 黃遏東, John Bradby Blake and the dream of a ‘Compleat Chinensis’

STORIES

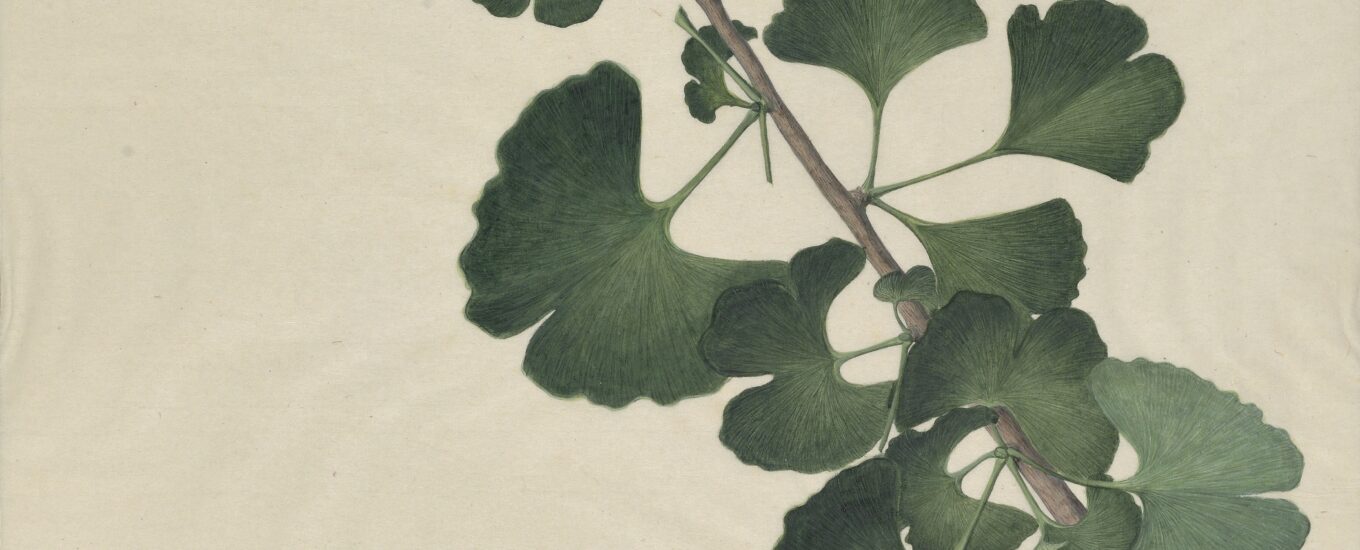

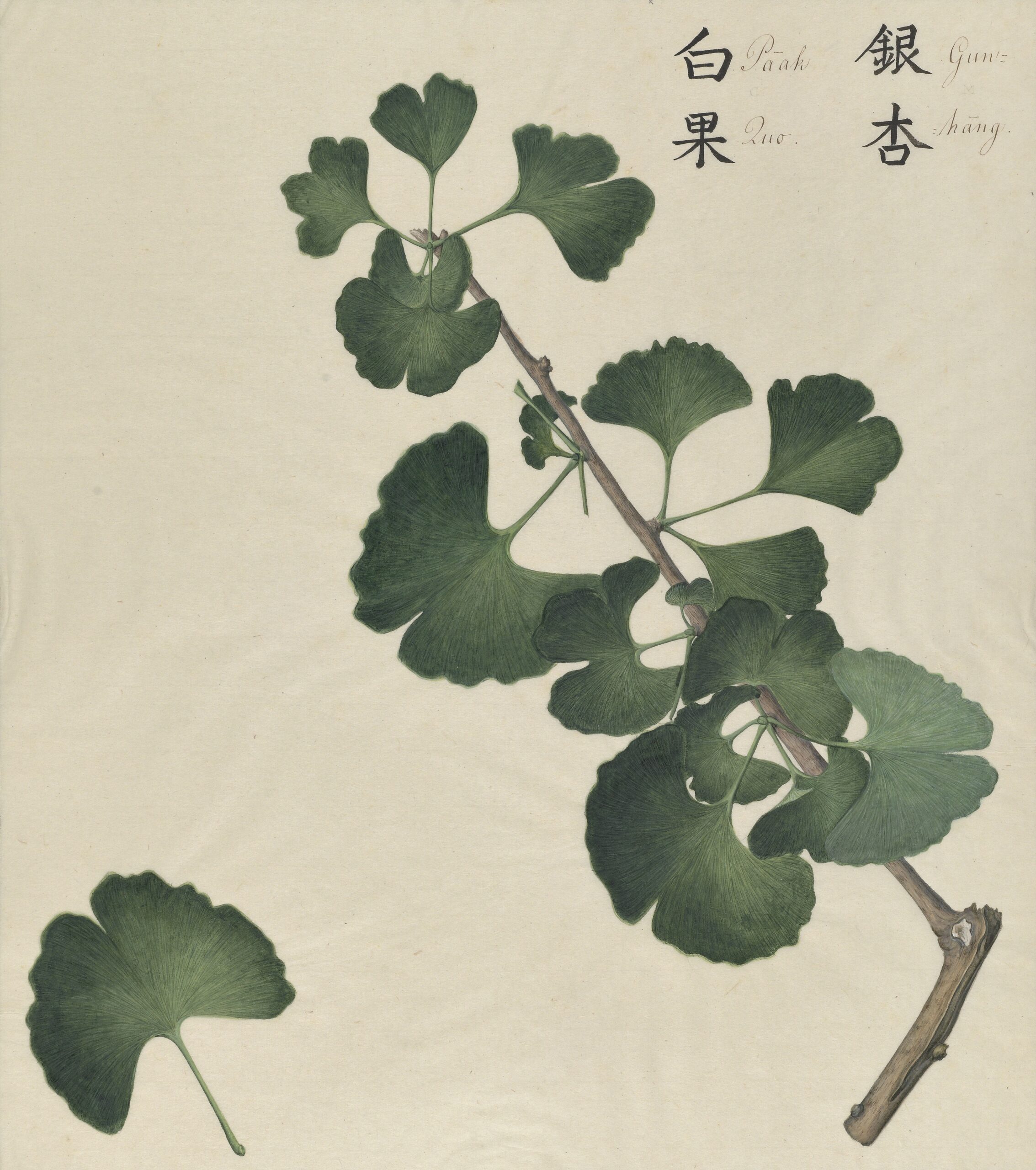

Gingko 银杏、白果 (1771), Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA

The beloved historian of Chinese art, James Cahill (1926-2014), once pleaded with his colleagues to examine not only what the greatest painters wrote about great art, but to scrutinize what they actually did as artists. We would find, he suggested, a great divergence between words and deeds, and a rich field of possibility for what even counts as art. The Painter’s Practice, as Cahill called it in the 1990s, has persuaded art historians to question how artists actually worked (more money was involved than they ever admitted), what they actually painted (much more than they owned up to), and what their interactions with merchants, officials, commoners, women, and foreigners may have been like (far richer than we expected).

As a result of Cahill’s challenge, today, art historians like myself recognize a far vaster range of images, ideas, and beauty than the artists themselves directed us to see. To me, the picture of art in China that has emerged is so different as to be almost revolutionary. One of those fresh new categories of Chinese art to explore is the thousands of botanical paintings created by Chinese artists in the port of Canton for Western naturalists over the course of the 18th and early 19th centuries. In my research on such paintings over the last fifteen years, the finest to have survived are those preserved at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, and on view for the exhibition Seeds of Exchange at the Garden Museum.

Gingko 银杏、白果 (1771), Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA

“Mauk-Sow-U”: this is the name of a painter that appeared in an article about botanical painting, in which John Bradby Blake’s project was mentioned only as one of many examples of naturalists who acquired paintings in China from Chinese painters. As would be obvious to students of the language, this “name” as it is written does not look or sound very Chinese at all, in any of the modern forms of transcription Chinese speakers operating in Western languages have had to learn.

In my search for the Chinese name that could stand behind this transcription, I was eventually directed to the historian Jordan Goodman, who, it turned out, was on a similar research quest himself. Through Goodman, I learned of Oak Spring’s marvelous collection of John Bradby Blake’s unfinished Chinese flora and its associated materials.

What is astonishing about this collection, to a historian of Chinese art, is the sheer detail it provides about precisely what Cahill called the “painter’s practice.” Through John Bradby Blake’s notes, we can reconstruct every visual detail demanded of the painter, how much time each part of the painting took, how colors were mixed, from whom Blake sought opinions on the quality of the paintings, and even the exact date each painting was made. We also find the painter’s apparent name: 麥秀 (Mandarin: Mai Xiu, Cantonese: Mak Sau). It is an extraordinary record, likely unprecedented in the archives of Chinese painting, of the specific demands placed upon a painter by his patron, and what exactly he painted.

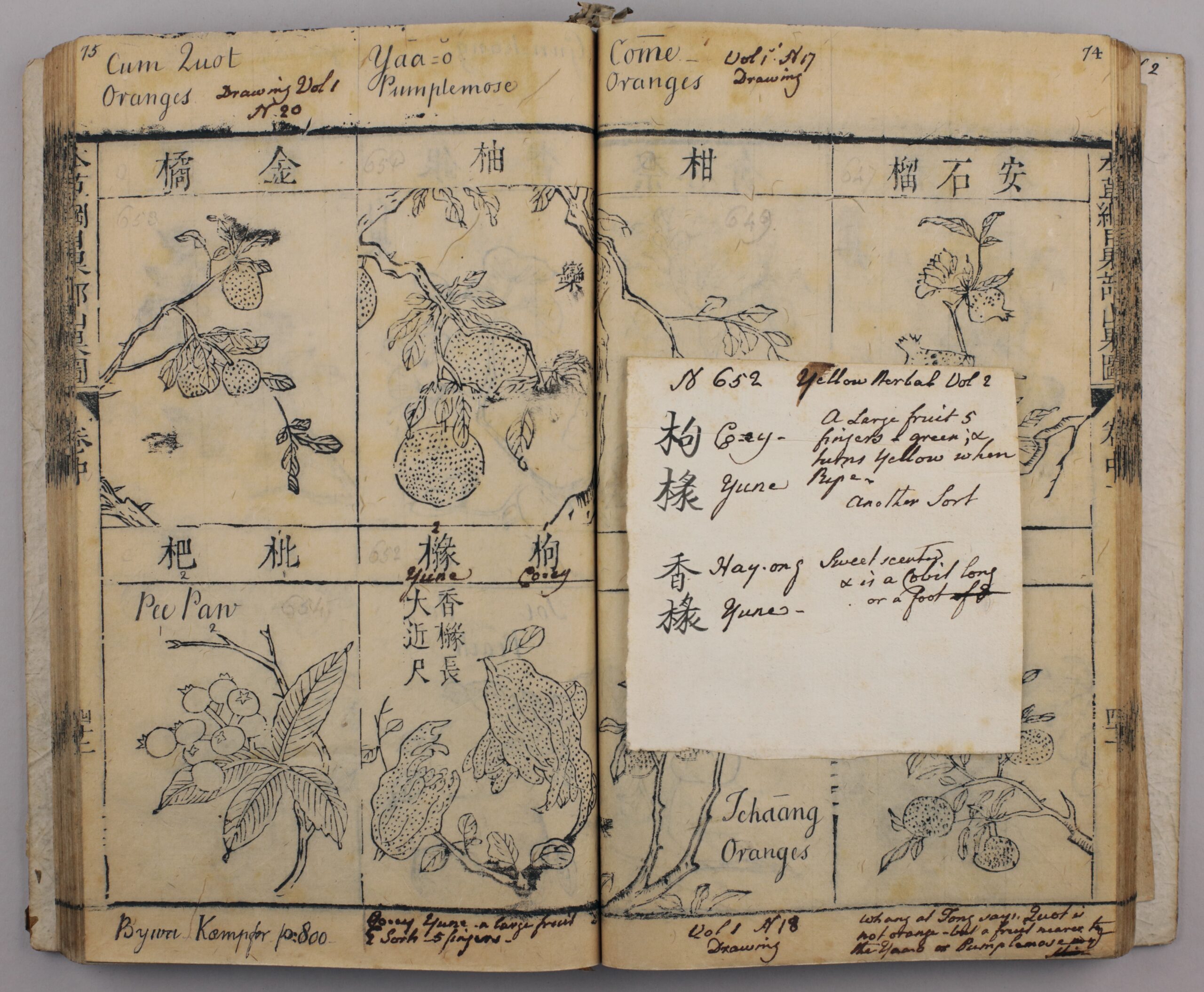

John Bradby Blake's annotated Chinese Herbal, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of Canterbury

But painters attend to more than their patron’s demands, and I realized it would be necessary to know what other paintings of flowers and plants Mak Sau 麥秀 the painter may have been looking at in the 1770s. The collection at Oak Spring includes a notebook which appears to be Blake’s personal notes on a Chinese book titled: 汪訒菴先生原本/增訂圖註本草备要/杏園藏板 [The Original from Mr. Wang Renyan / The Revised, Expanded, Illustrated, and Annotated Essential Pharmacopoeia / Edition of the Apricot Garden Collection].

From Blake’s notes, it was clear that he held an actual copy of this Bencao Beiyao [The Essential Pharmacopoeia], a somewhat surprising fact as Europeans in Canton at the time were supposedly prohibited from learning the Chinese language, and Chinese subjects were supposedly prohibited from teaching them Chinese language.

Although many editions of the Bencao Beiyao are preserved today in many libraries around the world, I could not find Blake’s particular title in the WorldCat catalogue, which includes collections from more than 10,000 libraries in 100 countries. This seemed so unlikely that I wrote letters to libraries whose records on their editions were not entirely complete, to inquire whether they indeed had that Apricot Garden edition. As it turned out, none of the librarians who answered me held the edition, and neither did I find any other books that had also come out of the “Apricot Garden Collection.”

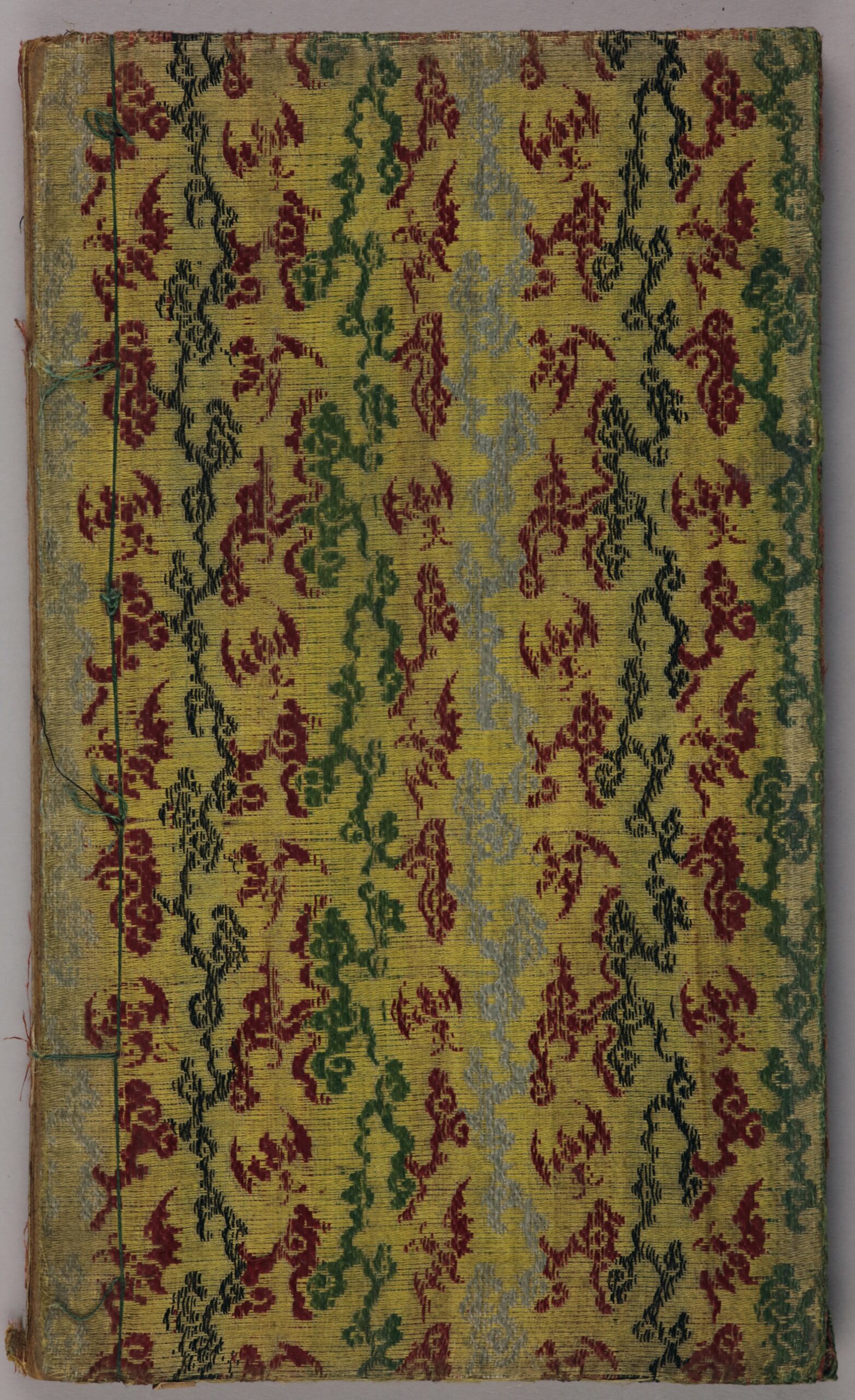

Floral silk cover of John Bradby Blake's annotated Chinese Herbal, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of Canterbury

My search for a Bencao Beiyao that Blake once read took over four months, but the ending was gratifying. I finally chanced across a 2008 blogpost by a Chinese student who was a master’s student in England. She blogged on the Chinese site Sinablog, in the heyday of Chinese blogging, when people of all sorts wrote and shared their daily thoughts and experiences about a wide range of topics.

She described a class trip to the Canterbury Cathedral Library, where a librarian showed her three Chinese books. She was moved to see that such old Chinese books were preserved in such a distant place, and took a photograph of one, posting it on her blog. The cover she had photographed was indeed the exact title and edition of the book Blake held a copy of, too.

Since I was in California at the time, I asked Jordan Goodman in London to visit Canterbury to see the book, so that we could understand what Blake and Mak Sau 麥秀 may have been looking at themselves when they were making their botanical paintings. Little did we expect to find not only the same edition of the book, but Blake’s personal copy of it! And not only that, during his visit, and with the archivist’s and librarian’s assistance, Goodman was able to identify more notebooks belonging to John Bradby Blake, sea charts and maps probably belonging to his father, Captain Blake, a complete edition of the Bencao Gangmu, the most popular materia medica in Chinese history, and even, a beguiling, three-dimensional miniature portrait of Captain Blake himself! Indeed, the collection of materials at Canterbury would turn out to be in every way as extraordinary as the collection at Oak Spring.

Seeds of Exchange installation view featuring Joshua Reynold's portrait of Whang At Tong 黃遏東, Graham Lacdao

The Garden Museum exhibition Seeds of Exchange: Canton and London in the 1700s is an extraordinary opportunity to see these two collections together, over two hundred years since Blake and Mak Sau 麥秀 produced the paintings together, and two hundred years since his father Captain Blake and the Chinese visitor Whang At Tong 黃遏東 worked together to assess it after John Bradby’s death. Now we can see not only how they worked, but even the visual and botanical resources they had to draw on, and the dedication with which Captain Blake and Whang At Tong 黃遏東 worked on John Bradby’s posthumous legacy.

Alas, their dream for a finished Compleat Chinensis was never realized: but if it had been, all of the unfinished drafts and notes would likely have been discarded altogether. They would never have been held onto by their descendants, eventually separated and sold, and found their ways to two distinct archives. And we would never have the opportunity to even guess at the “painter’s practice,” and all that might reside behind a beautiful botanical picture.

Winnie Wong is an art historian with a special interest in fakes, forgeries, and counterfeits. She is the author of Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (2014) and The Many Names of Anonymity: Portraitists of the Canton Trade (2026). She is professor of Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. See a selection of Winnie’s writing: winnie won yin wong

Seeds of Exchange: Canton and London in the 1700s is open until 10 May 2026