For me though, it was a revelation. In these high-windowed rooms, laid with McEwen tartan carpet and antique rugs, hung with mirrors and good paintings, a herd of elegant teenagers glided about, talking, laughing, smoking cigarettes, with drinks in their hands. Unimaginably, the drinks were in glasses made of glass. Someone was playing the piano, from the unsullied top of which nobody had removed the photographs and ornaments. In one corner, a chess game was in progress.

The reason I mention this is because it illustrates something important about the atmosphere emanating from Rory and Romana, his wife. More than anything, what it showed was trust. A conviction that if you believe in the innate worthiness of people, if you believe they are talented and curious and interesting and respectful of beauty – they will not disappoint you.

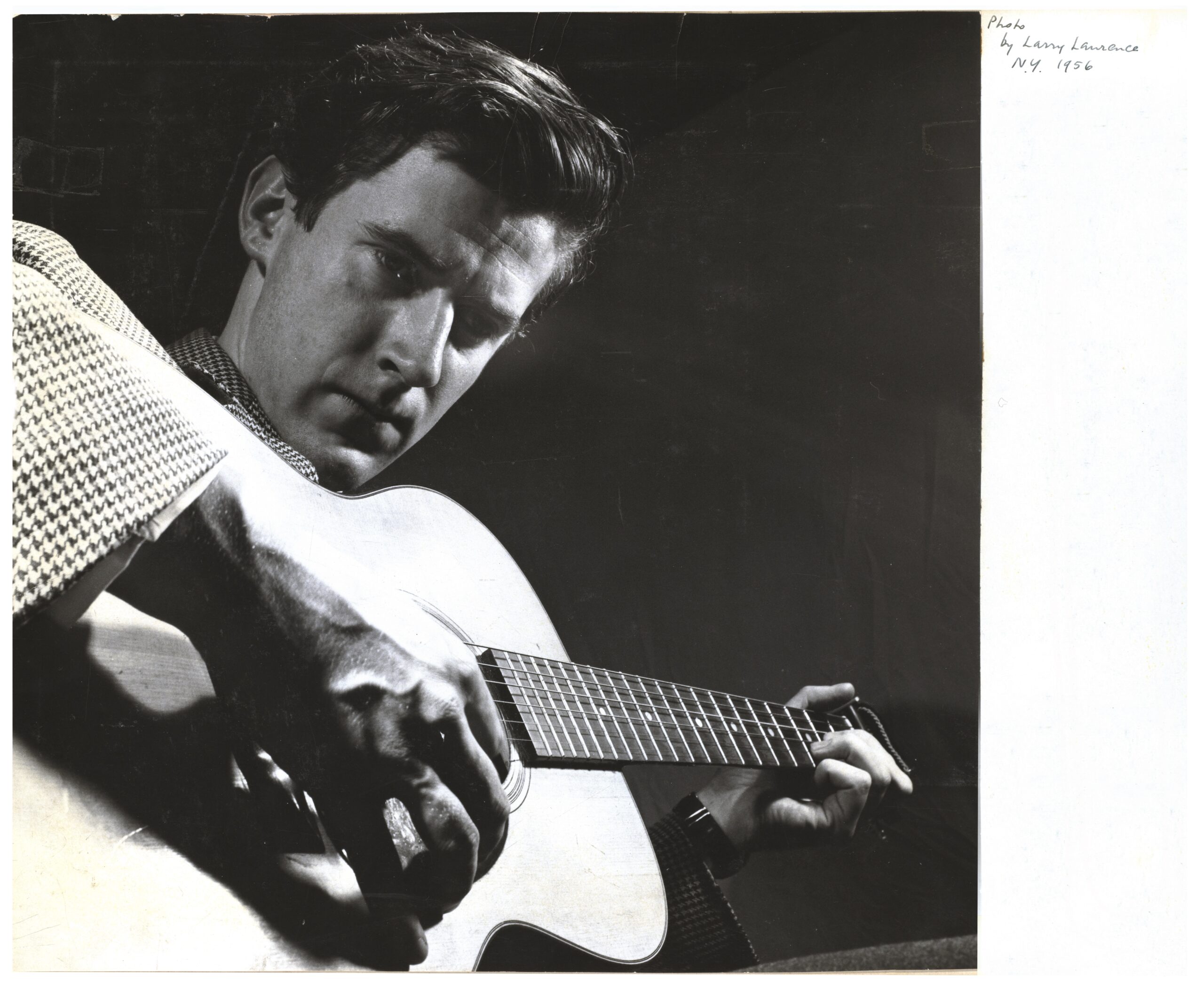

The same atmosphere pervaded Bardrochat, (pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable), the house the McEwens bought in South Ayrshire, which would fill with guests who, in addition to the normal country things of walks and fishing (Rory was an expert and devoted fisherman), were encouraged to paint, draw, write and make music. The musician David Ogilvy, a protégé of McEwen’s who first visited Bardrochat at thirteen, remembers the enchantment of this house, filled with visiting artists and musicians, and all the McEwen children making art and games, often led by Rory, as the place where his musical gift was first taken seriously, and art considered not as a side-talent, but as a contender for the real business of life. “Artistic endeavour had a high value in that house”, he said.