Vita Sackville-West and Richard Church: Neighbours, Gardeners and Poets

STORIES

By Rosie Vizor, Garden Museum Archivist

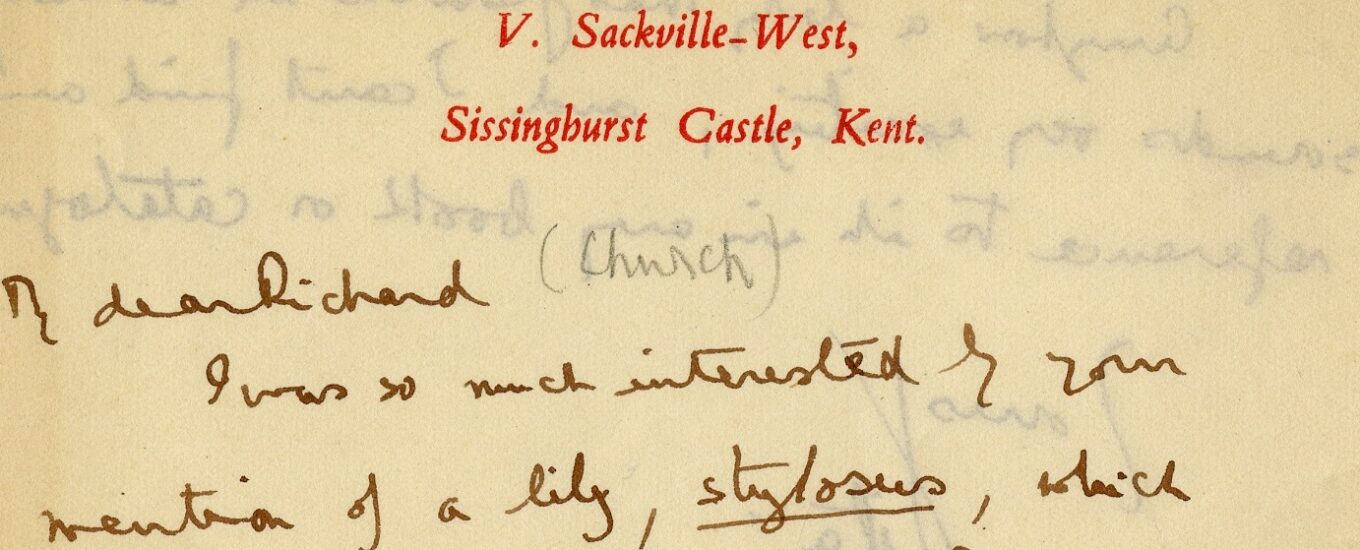

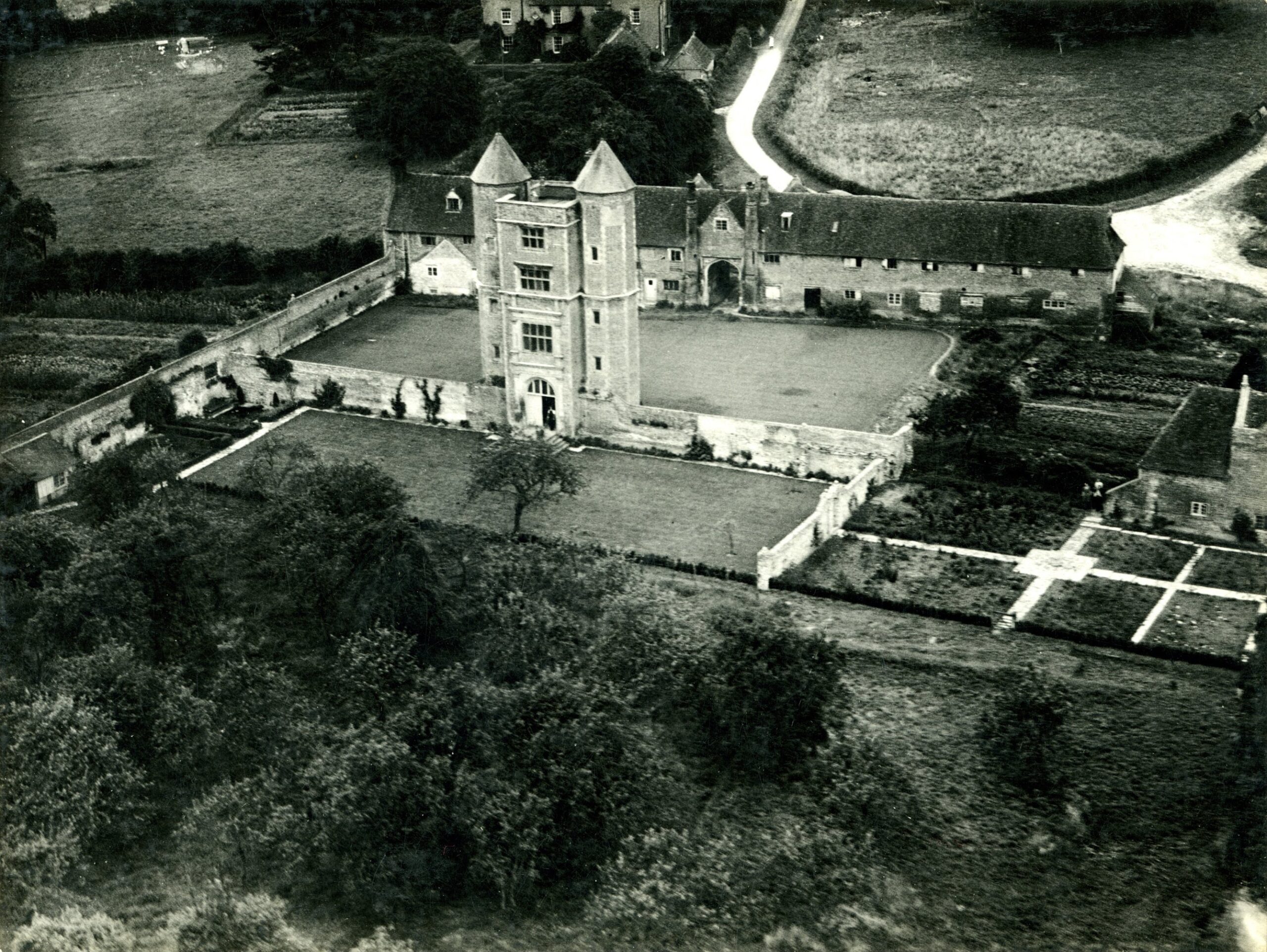

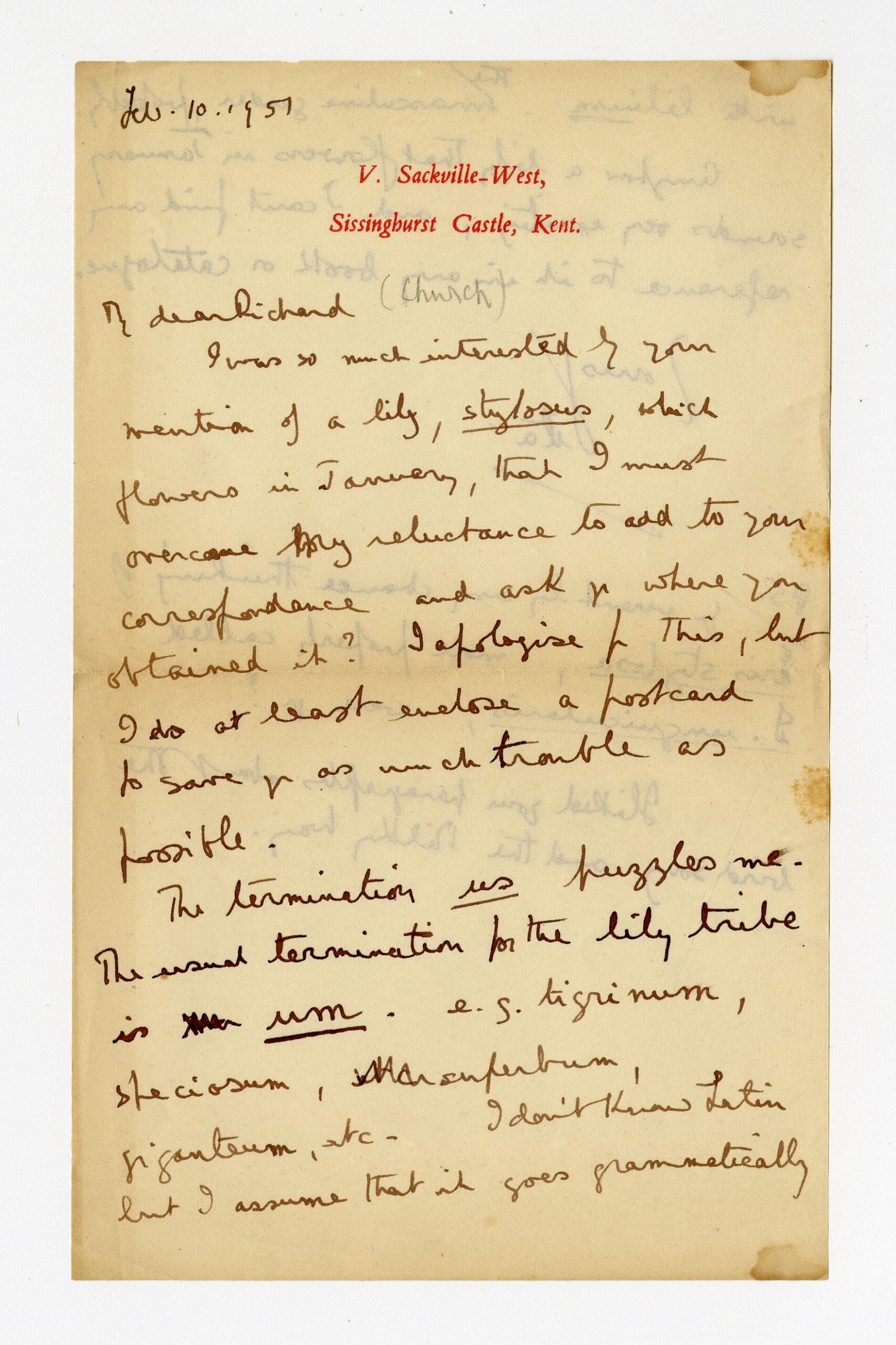

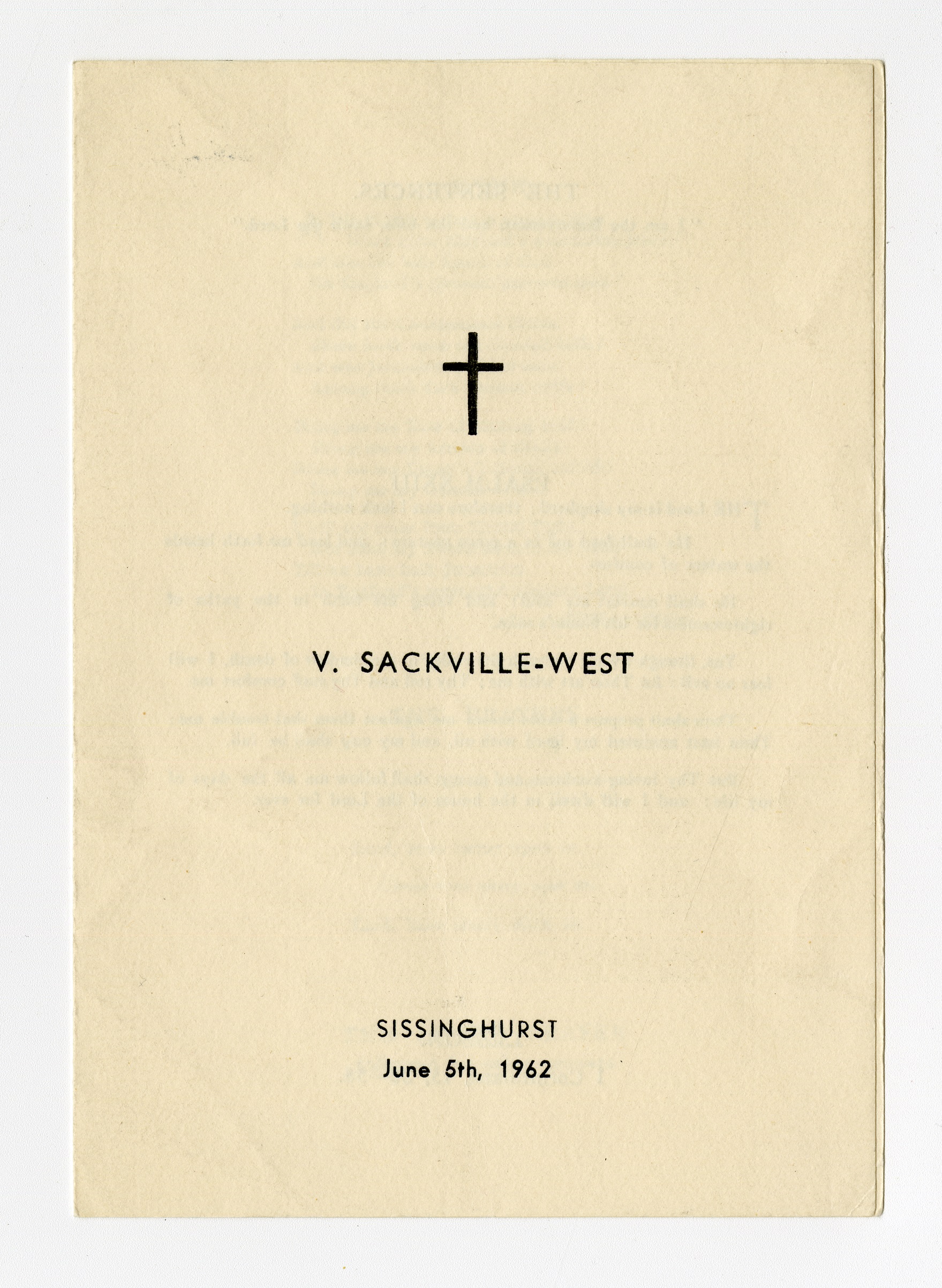

Despite the difficulties of the past year, the Museum has still been actively acquiring new material to enhance the Collection. When Garden Designer Paul Bangay alerted us to a Vita Sackville-West letter coming up for auction, offering to help us acquire it, we couldn’t resist. Even more enticingly, the letter was about an unusual lily. As it happened, the lucky person with the winning bid offered to donate the letter to the Museum – and more. This one letter opened up a whole story; there was another poet and garden-lover living within the grounds of Sissinghurst Castle, just a few steps from the main house – Richard Church. We are very grateful to Andy Moreton for his generosity, and would like to share some highlights from his gift here. Richard Church (1893-1972) was a poet, writer and critic whose love of the English countryside was evident in much of his work. He was born in Battersea into modest beginnings; his father was a postal worker and his mother a schoolteacher. He left Dulwich Hamlet School aged 16 due to economic necessity and joined the civil service, but wrote poetry assiduously in his spare time. Although his first book of poems, The Flood of Life, was published in 1917, Church carried on working for the Civil Service until 1933, 24 years altogether, until he’d built up a literary reputation that could sustain him as a full-time writer. The most acclaimed of his novels, The Porch (1937), drew on his experiences of working in the civil service. It was awarded the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize. Perhaps the most enduring of Church’s publications, though, was his three part autobiography: Over the Bridge received the Sunday Times Prize for Literature in 1955, The Golden Sovereign led to him being awarded a CBE in 1957, and the final volume, The Voyage Home, was published in 1964. For the last four years of his life, Church lived within the grounds of Sissinghurst, home of the famous poet, writer and gardener Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) and her husband Harold Nicolson (1886-1968). Church lived, fittingly, in the Priest’s house, which can be seen to the far right in the photograph below.

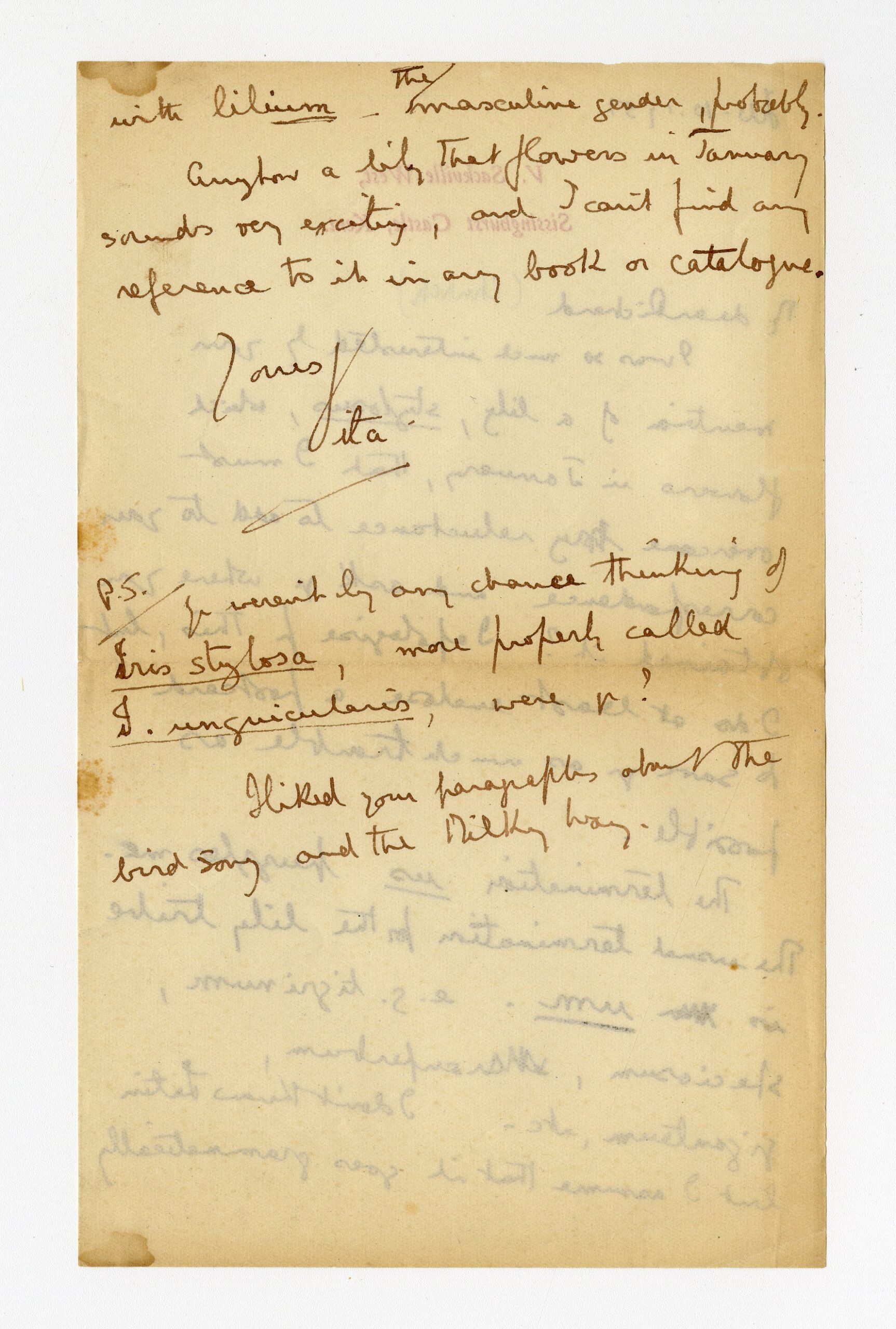

‘The termination us puzzles me. The usual termination for the lily tribe is um, e.g. tigrinum, speciosum, superbum, giganteum, etc. I don’t know Latin but I assume that it goes grammatically with lilium – the masculine gender, probably. Anyhow a lily that flowers in January sounds very exciting, and I can’t find any reference to it in any book or catalogue.’

Although Vita’s letter is enquiring in content, reading between the lines I wonder if she knew he’d made a mistake. She delicately questions his terminology in a P.S.: ‘You weren’t by any chance thinking of Iris stylosa, more properly called I. unguicularis, were you?’

Richard Church was also a prolific writer who travelled widely. He was the author of over 50 books spanning many different genres: poetry, novels, books about the countryside, children’s books, travel writing and literary studies, as well as being a respected journalist and critic.

Although the majority of Church’s literary archive is held at the University of Texas and Manchester University, a small packet of letters included within the Museum’s most recent acquisition provides a snapshot into his life, relationships, character and career. It’s a treat to read this poet’s well-crafted letters.

Although the majority of Church’s literary archive is held at the University of Texas and Manchester University, a small packet of letters included within the Museum’s most recent acquisition provides a snapshot into his life, relationships, character and career. It’s a treat to read this poet’s well-crafted letters.

They date between 1958 and 1969 and are all addressed to Jean Malins, Church’s long-standing secretary. Malins typed and edited Church’s work but the letters show she did much more, and the two developed a close relationship. Richard seems to have written to her once or twice a month while he was away, describing his travels and workload. Malins took care of his household affairs while he was gone, and he frequently checks in with her on matters like the pensions ‘request reminder rigmarole’, the refrigerator that’s ‘had it’ and ‘jockeying’ mechanics about his car. His caring nature is evident when he expresses deep concern for Jean’s wellbeing after her surgery, sending ‘deeply paternal’ love from ‘the old word-mongering tyrant who has tried your patience to the point of exhaustion over the past ten years or more’.

‘By now Christmas must have receded into the past, and you will be looking for signs of longer days; aconites and snowdrops, as heralds of hope. Here, the gardens of some of the private homes are a blaze of colour’.

Yet he is ‘mildly homesick all the time’, always longing to return home to the ‘solitude and peace’ of the English countryside, his major passion. He took part in many local activities in Kent, and made an effort to protect the natural environment. In his obituary written by friend Betty Massingham, she explains how one of his last efforts was to preserve a yew in Cranbrook Churchyard.[1] He was also deeply concerned with how gardening could become accessible for disabled people in his community. The annotated horticultural advice booklets within the archive hint at his own keen pleasure in gardening.

ALLOTMENTS by Richard Church

LIFTING through the broken clouds there shot

A searching beam of golden sunset-shine. It swept the town allotments, plot by plot, And all the digging clerks became divine – Stood up like heroes with their spades of brass, Turning the ore that made the realms of Spain! So shone they for a moment. Then, alas! The cloud-rift closed; and they were clerks again.

—